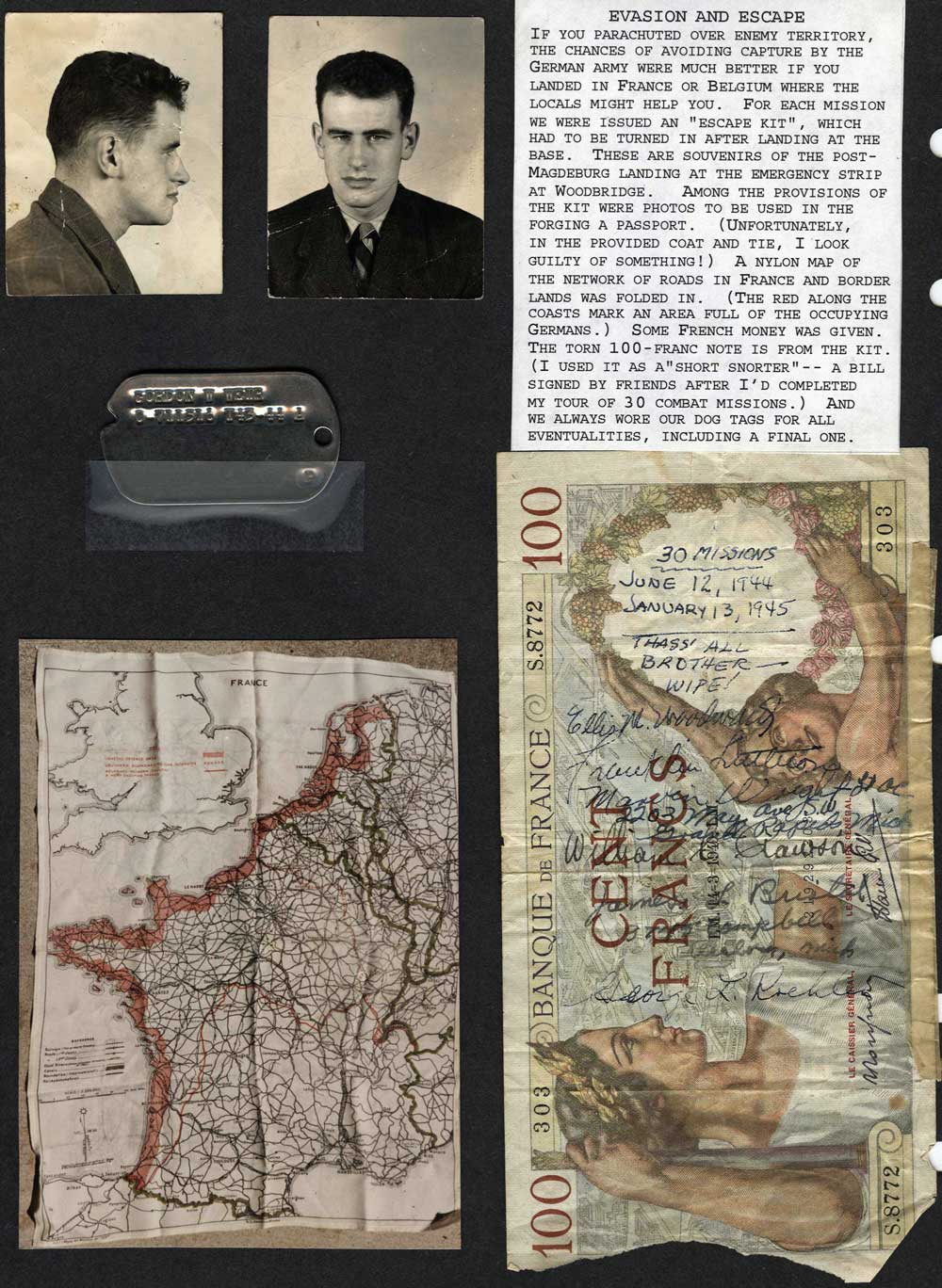

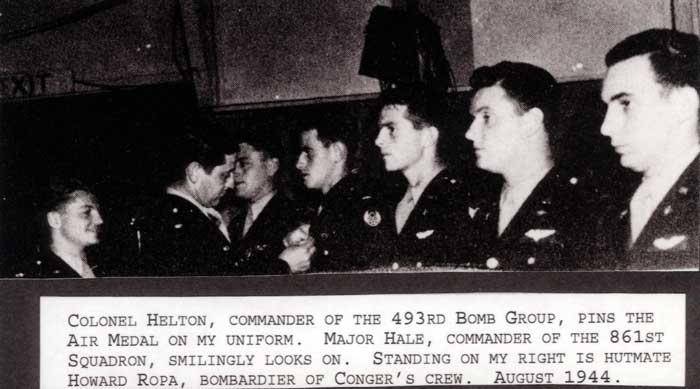

B-17 Cut-away View and Views of Cockpit and Bombardier's Compartment

Inside, arrangements were much like those on our Liberator. The chief difference was the absence of power turrets (with a gunner inside) at both nose and tail. Ours was the latest model Flying Fortress, the B-17G, armed with twin 50-caliber guns in a chin turret. Besides aiming our bombs, bombardier Mike Wright was to manipulate the turret with controls resembling handlebars of a bicycle. Mike's station was directly behind the large plexiglass bubble capping the nose. The Norden bombsight, by which he could fly the plane on the run to the target, was mounted in front of him. On either side of his seat were levers and panels of dials and switches feeding data to and from the Norden.

I sat on the left, behind Mike, my charts, protractors, circular slide rules, and log spread out on a shelf-like desk. An airspeed indicator, altimeter, radio compass, and driftmeter were at hand for dead reckoning. To my left was our trap-door entrance to the nose. It could also serve as our emergency exit; indeed, in common parlance it was the "escape hatch".

We could get to other parts of the plane through a passage around the bulkhead separating us from the cockpit. Behind the bulkhead, above us on the left, sat Woody at his command post. Bill assisted him from the right-hand seat. Mike and I could wave to them from the plexiglass dome for my sextant. The pilots were fronted by a complex array of instruments and controls and looked out of windows that were none too large. Sergeant Vales, as engineer, usually stood behind them monitoring the engine gauges. In combat he climbed into the top turret.

Behind Vale's station was the bomb bay. A narrow catwalk led aft. Mike would balance on this catwalk as he removed cotter pins from the arming mechanisms of each bomb.

Stations for four airmen were in the rear of the plane. Sergeant Sutton, no longer needed as a gunner up front, worked the radio at a desk behind the bomb bay; he also fired one of the two pivoting waistguns. Just aft of the radio desk, Sergeant Archer climbed down into the powered ball turret as he did on the B-24. Farther back Sergeant Spinney stood opposite Sutton at the other waist gun. In the narrow confines of the tapering fuselage Sergeant Kenawell handled the twin 50s at the tail.

When we converted to B-17s, Sergeant Smith, our first radio operator, transferred to another crew. Except for Smith's transfer, our crew stayed together as a unit from early practice in Nebraska through our last mission into Germany. Transfers and replacements were not uncommon, even though the Eighth Air Force aimed to assign permanent personnel to each plane. Other bomber commands relied on different pickup crews for each mission. Fortunately, our crew maintained its identity as a combat team.

As for our feelings about the B-17 versus the B-24, we admired whatever plane we were flying. The 24 could carry more bombs farther and faster, and its front and rear power turrets meant that it was better armed than the 17. Nevertheless, we instantly liked our new Flying Fortress, amusingly named "Ramp Happy Pappy". The pilots found it easier to fly. Mike and I liked it for the increased visibility from the nose. We could make ground checks more easily. We all believed that the 17 was a rugged plane. That proved true.

For a brief period the 493rd and other B-24 groups in the Third Air Division stood down. The war went on without us as we became familiar with our new machines. The transition went quickly, and the group was commended for it. Less than three weeks after receiving our Flying Fortress, we were riding it through the flak on our fifteenth mission.

Mission 15

On the 12th of September our crew was up for our first mission in "Ramp Happy Pappy". We were to lead the low squadron. In the briefing room the long red tape stretched to a city named Magdeburg. The target was a munitions plant on the Elbe River. If we took it out, fewer shells might be thrown at us on future missions. Our force made landfall farther north than usual, on the German coast near Wilhelmshaven. Then zigging and zagging around known gun batteries, we followed the Elbe up into the heart of northwestern Germany. The 493rd was to be the second group over the target. The skies were cloudless, a boon to the bombardiers aiming from above and to the AA gunners aiming from below.

All went well until we neared the I.P., the Initial Point, a ground feature over which begins the bomb run to the target. We were then about 50 miles southwest of Berlin, and I fancied that from my five-mile-high seat in the sky I could see Potsdam and the Nazi capital.

At the turn over the I.P., standard operating procedure was for each group to separate into three squadrons for the attack. The lead squadron goes in first; the high squadron then follows, and the low squadron heads in last. The group ahead of us had already shaken out into the bomb run. Our lead squadron swung toward the target. I heard Woody wonder aloud, "Why don't they turn? Why don't they turn?" The high squadron, impeded by winds or other troubles, seemed late in bending toward Magdeburg. Meanwhile our squadron had to veer off so the high squadron's bombs would not fall on us. When we could finally make our turn, our new course took us into a violent headwind that slowed our approach to the target to an agonizing crawl and separated us from the squadrons ahead.

My job on the bomb run was to help Mike pick out the target, but Mike quickly identified the buildings near the river. Then, for a while, we had little to do but wait and watch. Up ahead the flak was fierce. "So thick, you could walk on it!", we'd wisecrack after a mission, but not when we were flying into a blackening sky. The squadrons in front of us were being lashed by shrapnel. Suddenly, one of their B-17s burst into flames and then exploded. Nothing was left but four thin, black streaks as burning engines plunged earthward. Off to the side another 17 was twisting down. I wondered how many men were struggling to get out, held back by the force of the spin.

Our turn came. Around us flashes of red blossomed into black columns of smoke. Our plane bounced in the turbulent air. I felt a sharp thump, meaning the plane was punctured. Mike was bent over the bombsight taking aim at the munitions plant. The plane rose a bit as the bombs racks emptied. Instead of calling out "Bombs away!" Mike yelled, "I'm hit!" and began clawing away at his clothes to reveal the wound. I saw the hole in the Plexiglas and nervously relayed Mike's words on the interphone.

My message was drowned by an urgent call from Sergeant Kenawell, firing the tail guns, "Fighters! Fighters!" Then the intercom went dead. Our plane shuddered from repeated hits. A Focke-Wulf 190 flashed by over our left wing. Our plane nosed steeply down. I grabbed my parachute and tore open the escape hatch. What a long, chilling way down! Mike, too, was busy fastening his parachute. I was awaiting the command to bail out when Woody let us know that our precipitous descent of thousands of feet was because much of our oxygen supply had been shot out. (At 30,000 feet an airman dies quickly from anoxia.)

We were going on. I looked around. Of the eleven other planes in our squadron only one remained alongside. Great strips of aluminum had been torn off our left wing. Engines were leaking oil. The plane vibrated. One more blow from the fighters would surely finish us off. Where were they? All these happenings were but a minute of a lifetime.

I returned to my desk to find out exactly where we were and to figure the heading to England. Could we get there? Word was relayed that the elevators at the tail had been torn up. One of the bounces on the bomb run had been from a shell that had ripped through the bomb bay tearing out the rubber raft stowed above. If we ditched in the sea, we'd have only our inflatable Mae Wests to keep us afloat. Fragments of 20-mm shells from the fighter cannons had cut other holes in the fuselage. Splinters blasted from the plywood floor had cut Sergeant Sutton in the face. Over the intercom Sutton and Mike claimed their wounds were minor. More good news—Kenawell had destroyed an attacking Me-109.

The German fighters did not come back. Attacking 8th Air Force P-51s had driven them off. Now at our lower flying level we were an easier target for anti-aircraft gunners, but luckily we escaped further harassment by flak. To lighten the load we tossed out all the equipment we could spare. The waist windows were chopped out to make for easier exits. After four eternal hours England lay before us. Woody, uncertain of the integrity of the plane, had Sergeant Vales relay to the crew the option of bailing out. We all stayed. As Woody and Bill coaxed our riddled Fortress down to the long runway of the emergency landing field at Woodbridge, the rest of us huddled together on the plywood floor aft of the bomb bay, heads down, clasping our knees, waiting for whatever was to happen. As the plane touched down, George Kenawell jumped to a waist window. I hollered "Hold on!" He surely would have been hurt if he leaped out while the plane bumped and lurched at high speed along the ground. George stayed, though he called back, "But fire...?" He, too, had seen burning planes that day.

A smiling George Kenawell goes off to clean his gun.

A smiling George Kenawell goes off to clean his gun.Finally, brakes and tires gone, the plane slowed, swerved, and stumbled to a halt near an edge of the runway. We poured out full of amazed gratitude at our survival. As for our oil-stained, flak-lacerated Flying Fortress, "Ramp Happy Pappy" was happy no more; the remains were for the scrap pile. We owed much to the sturdiness of the B-17. If similar damage had been done to us flying a thin-winged B-24, we'd have fallen. [A few weeks later, the 445th Group flying B-24s was nearly wiped out over Kassel by the Luftwaffe. Only a single B-24 out of thirty-six escaped that disaster and made it back to England.]

Transcripts from official report of the Mission of 12th September, 1944—Magdeburg Germany

Mission 16

Two weeks after losing most of our squadron, we were again leading a formation into northwestern Germany. Replacement crews filled the emptied slots. Our assignment was to destroy a tank factory at Bremen. The battle at Magdeburg was much on my mind. The Bremen mission, number 16 in our count, was a most difficult one for me and perhaps for others in the crew. I was petrified as we headed into the thick flak over the target and exhausted by the time we rolled into the hard stand at Debach. After Bremen, I was in better command of myself and at least masked my fears. Fortunately, my duties as navigator kept me totally absorbed during much of our flights.

B-17s and fighter escort; this Air Force photo was taken on an earlier

mission to Bremen, but captures the essence of our post-Magdeburg trip.

Mike also faced the Bremen mission with foreboding. He rounded up extra flak vests. This twentieth-century armor consisted of metal plates sewn into heavy cloth. Each vest weighed a hefty 20 pounds but offered some protection against shrapnel. Mike lined our compartment with them. I appreciated the extra shielding, but Woody and Bill found the added weight forward made the plane more difficult to fly.

Our squadron's bombing on this mission was not good. A strong tailwind made for hurried aiming. Our bombs fell far from the tank factory, probably farther from the target than on any mission before or after. [Thus, months later after many more grim ventures over Germany, Mike and I were wryly amused when the Bremen mission was cited among the missions in which we earned the Distinguished Flying Cross for displaying "courage", "technical skill", "devotion to duty" in a "devastating" attack "destroying vital enemy installations".]

Back to Navigating Through World War II Home Page