Antashi Village, southwest of St. Petersburg

A RUSSIAN RIDE

Antashi Village, southwest of St. Petersburg

| If you were one of the few Americans traveling to the Soviet Union during

the height of the Cold War, chances are you would be carrying a guidebook

written in 1959 by Irving R. Levine. He would begin each chapter with a

little anecdote. My favorite is the one about little Ivan:

The story is told of the initiation of a group of youngsters into the "Pioneers,"

the grammar-school-age Soviet organization which includes almost all

of the nation's youth. Every youngster was asked the same set of questions. |

Back in Soviet times, you would have had to do a lot of paperwork (or pay someone to do it for you) to visit Russia. You would need sponsorship, hotel bookings, specified entry and exit dates, and pay a stiff visa fee. Nowadays with modern Russia opened up to the rest of the world...you still have to go through all of that nonsense! I did the paperwork before departing the USA; the faxes, service fees, and consulate fees cost nearly $100.

Equipped with my pricey Russian visa, I walked up (No cycling allowed at the border!) to the Russian border post in Narva, hoping that all would go well. It did. I filled out arrival and departure forms and I was in. Now for some rubles. No banks in Ivangorod border town, so I changed $20 cash with one of the fellows carrying a pocket calculator. Cycling was easy on the two-lane highway—gently rolling terrain past forest, hayfields, and rustic villages. I stopped for groceries at little store and was amazed how well stocked it was. After 96 Russian kilometers I pulled into a fir forest for the night and camped.

Even the wildflowers were big in Russia. After crossing from Estonia, I began seeing flowering Queen Anne's lace plants growing as high as three meters (10 feet). Taking a photo was difficult—I had to stand on an embankment to get a good shot.

I rolled and rolled into St. Petersburg the next day. It was a big place. Only after hours of seemingly endless suburbs did I reach the center and the St. Petersburg International Hostel. Staff here had helped me get a Russian visa. The hostel has a fine location near the east end of Nevsky Prospect, the wide street along which most of the famous museums and buildings of the city are located. I would have six more days to try and take it all in!

Even central St. Petersburg is huge—I put in a lot of walking as bus and subway stops were far apart. The underground metro here isn't as famous as the one in Moscow, but there are some terminals with marble halls and grand entrances (one looks like a round Greek temple). The subway escalators must be about the longest in the world—they drop up to 80 meters below the surface and can take as long as the actual subway ride. Most signs are only in Russian. My high school Russian paid off because I can read the Cyrillic alphabet. Actually many words are similar to English ones once one gets around to reading them.

On such long escalator rides, it has become popular to people watch—observing the cross-section of humanity headed in the other direction. Women tend to be very fashion conscious. If a woman has the figure for it, she'll often wear very tight and revealing clothing. Men don't bother much with fancy clothing—it's far more common to see a shirtless man is than one in a suit.

Walking around town seemed like trekking due to the distances. There's so much wonderful architecture, however, that a leisurely hike can be a lot of fun. Peter the Great founded the city on a swamp in 1703 as "Russia's window to the west." Peter had to first evict the Swedes from this corner of the Baltic Sea in a series of decisive battles, then he brought in the finest artisans and architects of Europe to build his new city. The layout resembles Amsterdam with its many canals, except here the streets are wider. St. Petersburg is the most European of all Russian cities, and remains Russia's cultural center. It has gone through a lot of revolutionary times, wars, and communism, surviving all. Now the city was celebrating its 300th anniversary.

The next morning I walked west along the main street of Nevsky Prospect, admiring the many baroque, rococo, classical, and countless other styles of buildings. Statues and faces and flora decorate many of the palaces and commercial structures. Eventually I came to the broad Neva River and crossed on a bridge to Peter & Paul Fortress. The tall, slender spire of the cathedral here marks the last resting place of Peter the Great and most Russian monarchs since. The fortress was intended to fend of the Swedes, but it never had to, and the fortress became a prison for opponents of the royals and later, those of the communists. The walls now enclose several museums, including one on rocketry (there was a research lab here in the 1930s).

The following day I did churches. My favorite was the Church of Resurrection of Christ, built 1883-1907. Unlike almost every other building in the city, this one displayed unrestrained Russian exuberance. Onion domes painted in bright colors towered over the surroundings. Inside, 7000 square meters of mosaics covered the soaring chambers. Most scenes depicted events in the New Testament or the many saints of the Russian Orthodox Church. The effect was dazzling. During Soviet times, the nutty communists turned this beautiful church into a warehouse! Now it's well restored. Its other name—Church on Spilled Blood—refers not to Christ, but to Czar Alexander II who was assassinated on this spot in 1881.

For grandiosity, it would be tough to beat St. Isaac's Cathedral. Work on the great domed neo-classical structure began in 1818 and took 40 years. The solid granite columns brought from Finland weighed 120 tonnes each; a model showed the special scaffolding used to set them in place. Marble (14 different types), malachite (16,000 kg. of the green mineral), and 600 square meters of mosaics cover the interior. The central painting on the ceiling measures 816 square meters. Very impressive! I climbed up to the base of the dome for a panorama of the city that stretched to the horizon. The Soviets during their rule had turned the church into an anti-religious museum!

Now for a day of history. The cruiser "Aurora" had taken part in the Russo-Japanese War, but earned enduring fame for firing the (blank) shot toward the Winter Palace in 1917 that began the October Revolution. I also visited the little log cabin built for Peter the Great 300 years ago. Next, a little spying. I headed into the Artillery Museum for a look at the many missiles and rockets among other exhibits. The early 1950s rockets looked like copies of Hitler's V-2, but more advanced models soon came off the production lines. I saw pieces of a certain American U-2 plane shot down in 1960. Most of the vast museum was devoted to the struggles of WWII, including the Siege of Leningrad (St. Petersburg). The city had triumphed during a two-and-a-half year siege by the Germans, though somewhere between 500,000 and one million inhabitants died from starvation, disease, or shelling during that time. My final stop for the day was at the nearby Naval Museum. A vast hall held one of Peter the Great's little sailboats—the beginning of the modern Russian navy—and many ship models. Smaller rooms illustrated periods of naval history to the present.

One museum, one with perhaps more art than any other in the world, kept me enthralled during an all-day visit. The Hermitage collection began with Peter the Great's donations and has been greatly added to—legally or otherwise—by later royals and especially the Soviets. It's said that if one viewed every piece for one minute each, then one would finish seven years later. The art begins with prehistory and ends with the present time. The Roman collection alone is huge, as is the 1st-century marble statue of Jupiter on his throne, maybe three meters high. I wound around the galleries through the Italian Renaissance, 17th-century Flemish and Dutch, as well as famous works from France, Spain, and Russia. I found the French Impressionist paintings especially impressive. Surprises cropped up now and then, like the giant Garuda god carved in wood by a Balinese placed next to a bust of a Roman emperor. By the time the museum started to close for the day, I was in the Asian rooms. Whew! Three palaces—the Winter, Little Hermitage, and Large Hermitage house the collection. They would be a major attraction even without the art—grand staircases, parquet floors, tons of marble and malachite, chandeliers, throne rooms, etc. With the art...well you really need to see it for yourself!

Then a day in the countryside. I took a bus southwest of town to the seaside palaces of Petrodvorets, a royal retreat started by Peter the Great. The Grand Cascade, behind the main palace, had thousands of jets of water spraying the air amongst gleaming gilt statues—a dazzling sight in the sunshine. The central figure, a muscular man pulling open the jaws of a lion (Do not try this at home.) was said to represent the victory of Peter the Great over the Swedes. Little palaces dotted the expansive estate, and one area had trick fountains where little kids tried to find the hidden switches. I kept dry with strolls through the formal gardens, parklands, and forest. Views across the blue Baltic took in the distant skyline of St. Petersburg and the naval island of Kronstadt.

On the last day, I hit the Arctic and Antarctic Museum with an old plane on skis, wildlife exhibits, and lots of photos on explorations and scientific work. Russia has a LOT of Arctic, so that was the biggest section. I spent the afternoon at the Russian Museum, a huge collection of Russian art from early icons to modern. That night I took a train to Moscow. I got confusing advice on how to bring the bicycle, but it turned out I could lay it flat on the compartment floor under the seats next to the window (with the front wheel and handlebars removed).

At 6 a.m. the next morning I was in Moscow, the political and financial center of one-sixth of the world. I checked into the Travelers Guest House hostel, then hopped a Metro to Red Square and the Kremlin. It seemed like half of the buildings that I passed near Red Square were churches. You've seen pictures of St. Basil's Cathedral, the one with the crazy colored and patterned onion domes. The brick structure has a central chapel surrounded symmetrically by eight smaller chapels and a ninth tacked on to one corner. The interior has some pretty icons, but nothing to compare to the riot of colors on the outside.

Red Square and the Kremlin turned out to be confusing at first, as access was restricted for security or something. The long (1-1/2-hour) line for Lenin was daunting too. I put them off until later days, and ducked into the huge Neo-Russian brick building that housed the History Museum. It covered early times with lots of prehistoric jewelry and spear points, and the emergence of Russia. Upstairs, a motley assortment of exhibits covered such diverse fields as ancient Greek pottery and French space exploration. No English labels in this big museum, as is typical in Russia despite us foreigners paying premium prices.

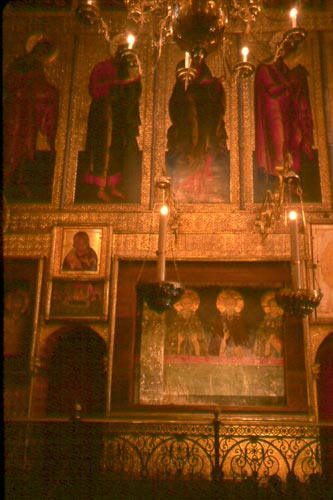

The next day I was ready for the Kremlin. Only tours could go inside, so I paid $30 for a fast-paced three-hour trip into the heart of Russian power. I passed the official residence of the Russian president, though Putin actually lives on the west side of Moscow. Next I gazed in awe at the enormous Tsar's Cannon (built to intimidate, but never fired) and the Tsar's Bell (never hung or rung). Each must have weighed hundreds of tons in bronze. The Kremlin contains the most important church in Russia, and I got a look inside at the many icons, royal thrones, and gilt. Lastly I gazed at the glittering objects in the Armory—pearl- and jewel-encrusted thrones, robes, bibles, coaches, and other royal necessities. Exhausted from the dazzle, I recovered in a good vegetarian restaurant.

That evening, I hopped on a tour boat for a cruise down the Moskva River, passing parks of relaxing Russians, churches, the Kremlin, and Moscow's incredibly varied architecture.

Cities don't get much bigger than Moscow. Fortunately the underground Metro is fast and efficient. Like the one in St. Petersburg, the Metro lies deep underground. Many of the central stations have beautiful decoration—marble walls, stained glass, ceramic bas-reliefs, and colorful mosaics. This Soviet art was to help promote the Communist way of life and show the bright future ahead.

Every self-respecting tourist HAS to visit Lenin, and I was no exception. After a 30-minute wait and three security checks, I walked across Red Square to the low pyramid of stone. Steps led into the cool depths, where the life-like, though pale, Lenin rested under the spotlights. Every hair of his short beard seemed perfectly in place. Back in the sunlight, I was sheparded past memorials of Soviet greats such as Brezhnev and the cosmonaut Yuri Gargarin, then a long stroll across Red Square. It's not actually red; the Russian word for red originally also meant "beautiful."

Curious about Russian space exploration, I headed to the Memorial to Soviet Cosmonauts. A soaring titanium spire had a little rocket ship on top and bas-reliefs of a cosmonaut and engineers at the bottom. Inside a large, dimly lit hall, I found many of the landmarks of Soviet space exploration. A model of Sputnik began the story. Two capsules on display had carried dog passengers a year before Gargarin took to the skies, and of course there was the re-entry vehicle of Gargarin's pioneering flight in 1961. Early unmanned spacecraft that had flown to the moon, Venus, and Mars had chalked up many space “firsts.” I also saw some of the parts of the USSR-USA Soyuz flights. A video showed life on the Mir space station.

The four days in Moscow passed quickly, and I would have liked to stay longer and seen the famous art museums of European and Russian works. I did get to one art museum that was a surprise because I hadn't known of it beforehand—the one of Nicholas Roerich, the Russian mystic who spent many years exploring and painting the Himalaya in the early 20th century. I had visited his house and gallery in the Indian Himalaya the previous year and liked the works very much. No two paintings seem even remotely alike. The Moscow collection had many Himalayan landscapes plus some Russian religious and human subjects.

The more that I see of the Russians, the less that I understand. Some ten years ago I flew Aeroflot between New Delhi and Bangkok—the cheapest ticket then. During the 3-hour flight I watched, out of the corner of my eye, to see if any of the stewardesses would smile at any time. Nope. Russians in public do tend to put on a "carrying the weight of the world" expression. They have the happy face only in private, though youngsters in love don't hide it.

Quick service is not a tradition here. Russians are used to having to wait in slow-moving lines. Not that they like it—they'll quickly cut in front of you if they think they can get away with it! My worst experience was at the famous Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg. After waiting almost an hour in a very long line to get in, I found that only half of the ticket booths were staffed. A few sights have a special foreigner counter, which can save a lot of time, but not this one.

The Russian attitude to foreigners is also perplexing. Do they fear us nowadays? The government does nothing to encourage tourists. When did you last see a "Visit Russia" poster published by the Russian Tourist Agency? Actually, there's no tourist promotion office. I wonder if there might be a Tourist Demotion Office in some dank corner of the old KGB office! You really have to WANT to visit Russia to come here. The visa takes an awful lot of red tape, then it must be registered, or you'll have trouble getting out. I never found a tourist office. Intourist and other agencies are only here to make money by selling tours and other services. And foreigners get to pay special prices, which can be quite exorbitant—up to ten times as much as a Russian would pay. The best-known museums and sights have the highest markup. Hotels in the big cities are tough on the wallet. The only good ones have international partners and cost $200 a night and up. Cheaper hotels are said to have awful standards. The only option for me in St. Petersburg and Moscow were hostels, and there were only a handful of these. Moscow is the priciest place in Russia; costs for most services tend to be at European levels. The only bargains are the Metro and Lenin's Tomb.

No bike routes that I know of led out of Moscow—I was on my own. First, I just had to ride past St. Basil's Cathedral, Red Square, and the Kremlin! Then I followed a paved path upriver along the Moscow River for several very pleasant kilometers. Next came the hard part. Moscow is laid out with radial highways leading from the center to the countryside and connecting with several circular roads. Vehicles totally packed the fast-moving traffic on the radial highways, so I had to find a parallel way on dirt paths, parks, frontage segments, and sidewalks. (Russians drive and park on the sidewalks, so a cyclist didn't attract any notice!) Finally I passed the last ring road and the last McDonalds (I earned that large chocolate shake.) Traffic was still heavy, but I was now out in the forested countryside headed west to St. Petersburg. That afternoon I had the luxury of wheeling into a room at the Zvenigorod Hotel and plopping down in the restaurant for a good dinner. No hot water in the shower, however; a $13 room doesn't always buy luxury in small-town Russia.

The next morning I stopped at a monastery just outside Zvenigorod. A high wall and towers with gun ports still enclosed the church and monastic buildings. The place seemed very popular with Russian tourists, many of whom attended the morning service in the beautiful Russian Orthodox church. The priest's chanting was interspersed with beautiful singing by a women's choir, sounding much like what one would expect from angels. No pews in Russian churches, so everyone stood; people casually wandered in and out.

That evening I was looking for a hotel in Volokolamsk, when I asked a woman where one might be. She spoke English (a rarity in the countryside) and immediately invited me to her house with her sister. Tamara was from Moscow, but her folks were from here and now this was her summerhouse. I got a tour—and taste—of the large garden behind. Besides the expected potatoes and cabbages, she had dill (for pickles), cherries, red currants, black currents, and raspberries. Tamara liked to travel and had taken advantage of post-Soviet freedoms to visit Western Europe. America was too far away, and she was afraid to fly due to terrorists.

By the third day I was out in the countryside bouncing over a rough gravel road. Ice-age glaciers had smoothed off the land so only low uplands remained, but these were the source of many rivers, including Russia's greatest, the Volga. Country houses often had fancy wooden trim, sort of a Russian gingerbread. Log houses were common; their finely crafted logs fitted precisely to keep out winter's chill. Villagers had electricity but many had to draw water from a well or communal spigot. For me, the fine summer weather continued and I enjoyed a night camping. So the days rolled by. Summer ended after five days, however, and cool showery weather took over.

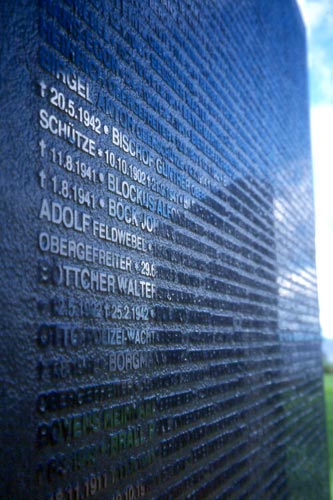

I often saw WWII memorials in both town and countryside. This part of Russia had been under German occupation with enormous loss of life, property destruction, and looting of cultural treasures. Many German soldiers never made it home and were left behind in mass graves. I passed three of these, which had been recently made into memorial parks. The most memorable one overlooked vast Lake Ilmen near Staraya Russa. Groups of three stone crosses marked each section of the site. In the center, large slabs of polished black rock listed alphabetically the names, dates, and job of each of the hundreds of soldiers here.

When the good citizens of Novgorod (New Town) named their place more than a thousand years ago, they never dreamed that it would one day be the oldest Russian town! Around A.D. 1000 it became such an important trading center that the merchants were able to do away with the nobility and make the town a republic. The strong walls of the kremlin (fort) kept out greedy invaders for nearly 500 years until Moscow managed to take the town over and end the republic. Novgorod is now full of old churches and museums. I was most impressed with St. Sophia's church, which dates back to the early days and now has daily services in its towering hall.

In 13 lucky days I completed the cycle trip across the corner of Russia between Moscow and St. Petersburg! The ride went very well despite some voracious mosquitoes and a few rough roads. I rolled into St. Petersburg via a back road to the Neva River, then a highway beside the river into the center of the city. On the way I passed a dozen river cruise boats at their berths; each huge boat had four decks. Perhaps I'll take one somewhere next time I'm in town!

I had to leave Russia by the 16th of August, when my visa expired, or I would be in big trouble. How big, I don't want to find out! So after one night in St. Petersburg, I hit the road again and followed the Gulf of Finland westward. A ray of sunshine broke through the clouds and fog as I wheeled out of central St. Petersburg. I crossed the broad Neva River, then followed sidewalks along one of its branches toward the Baltic Sea. Soon the paths ran out and I was in the thick of the traffic of M10 headed toward the Finnish border. After a few hours the main highways branched inland and I enjoyed some tranquil riding along the Gulf of Finland. The sun came out too. Wealthy Russians had dachas (summer houses) along the park-like towns here. Farther out, I was in thinly inhabited forests of conifers and birches with occasional views of the sea.

The next day brought more sun, forest, and coastline as I headed for Viborg, an old Finnish town lost to Russia around 1940, regained with German help during WW II, then lost again at war's end. I stayed on an old passenger boat, with stained-glass skylights and pretty woodwork inside, that had been converted to a hotel. The next morning I strolled the cobblestone streets in the sunshine admiring the architecture of the old buildings downtown and nearby Viborg Castle. The castle had a tall octagonal tower with fine views and a large museum of history, nature, and art. Shortly after entering the castle, clouds moved in and the skies let loose a three-hour torrent of rain that flooded streets and even the art gallery. I stayed in the castle until the worst of the rain was over, then headed back into the soggy downtown. A light rain continued to fall and it was 3 p.m. What to do? The boat hotel was booked out for the weekend (it was Friday) and the Viborg Hotel wanted an extravagant $75 for a single room. So I turned the front wheel toward Finland and splashed my way out of town. The rain soon stopped and I sped down the M10 across forested hills.

Villagers sat along the roadside selling stacks of wild mushrooms along with jars and buckets of blueberries. Russia is a land of small traders. It's a common sight to see people selling produce and forest products along roadsides. Little stalls in town markets offer clothing and most everything else.

Even if summer is short in Europe's north, the days are long and the sun stays out nearly to 10 p.m. By 9 p.m. I neared the international border, loaded up on cheap Russian chocolate bars and other groceries, and wobbled over to Russian immigration. Everything went smoothly, much to my relief, and I was soon in Finland. The air instantly seemed cleaner and the countryside was nearly litter free. I pitched my little tent in a mossy forest about five km into Finland.

So how was Russia? Fascinating, of course, but also a bit tiring. Air pollution from factories and vehicles was much higher than in Western Europe. Roads could be poor with broken or non-existent shoulders. Also there were few people to talk with—hardly anyone outside St. Petersburg and Moscow speaks English, and I only knew a few words of Russian. The physical and mental health of the Russians should be better—there's a lot of smoking and drinking, and people sometimes lack the spark of life. How could Russia ever have been a superpower? Today it is a developing country, though developing at a slower pace than most third-world countries. While the government certainly was unfriendly to us tourists with the visa and registration hassles, individual Russians often proved very friendly and helpful. So I'm glad I went, but I'll probably wait for things to improve before returning.

Matryoshka dolls in a St. Petersburg shop window

Detail of the Winter Palace, commissioned in 1754, and now one

of four buildings

housing the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg

Nevsky Prospect in the center of St. Petersburg

Church of the Resurrection of Christ (built 1887-1907)

in St. Petersburg

SS Peter & Paul Cathedral in St. Petersburg

The Baroque interior of SS Peter & Paul Cathedral

Samson pulling the lion's jaw at the Grand Cascade

of Petrodvorets, southwest

of St. Petersburg

Golden domes of Moscow's Great Kremlin Palace and churches reflect the sunset.

St.

Basil's Cathedral in Moscow

Cathedral

of the Assumption in the Kremlin

Memorial Museum of Cosmonautics in Moscow

Yuri Gargarin's tiny reentry capsule used in his 108-minute orbital flight of 12

April 1961

That's one of his training suits on the right; Memorial Museum of

Cosmonautics

Bilka (stuffed in glass case on right) flew in the red and silver capsule in 1960;

Memorial Museum of Cosmonautics

Church at Savvino Storozhevsky Monastery, just west of

Zvenigorod.

The monastery was a busy place. I attended part of a Russian

Orthodox service inside.

Abandoned churches were a common sight in the countryside.

This one near Stepurino looked beyond repair.

Tamara

in front of her old house in Volokolamsk

Volga

River at Staritsa

These students from St. Petersburg were on a short cycling tour.

I only saw

three other touring cyclists during my month in Russia.

German

mass grave from WWII

One

of the six stone slabs from the German mass grave

Church

of St. Nicholai, built 1113-36 in Novgorod

Church of the Nativity of Our Lady from Perdky (1531)

at the Museum of Popular Wooden Architecture, south of Novgorod.

Two staff at the Museum of Popular Wooden Architecture

Ekimova's House (1882) from Rishevo at the Museum of Popular Wooden Architecture

WWII

memorials dot the countryside.

Vyborg

Castle, built by the Swedes in 1293

Sunshine in the morning, heavy showers in the afternoon—view from Vyborg Castle