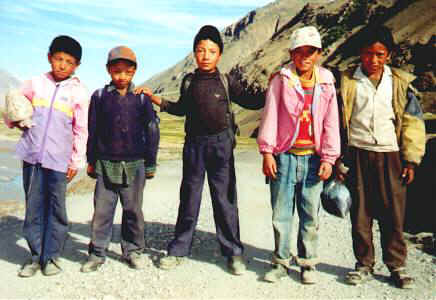

boys of Zanskar

boys of Zanskar

To Zanskar and back with Bill and Bessie Too

Leh, Ladakh, India

8 September

2002

Bessie Too and I returned yesterday from an epic ride down the Indus Valley and up among glacier-clad mountains and alpine valleys. We bounced our way into the heart of Zanskar—one of the Himalaya's most remote regions.

It all began three weeks ago with a ride out of Leh. I dropped down to the Indus, only to leave it a short way beyond and climb into colorful desert hills of a wide valley. The road swung back to the steep walls of the inner gorge and a panorama of the confluence of the Zanskar and Indus Rivers. Although the Zanskar River flowed from my destination, no road followed its deep canyon all the way through to Zanskar; I would have to follow a long roundabout journey.

Alchi Village was my first overnight. The small temples here date back to the 11th century and house some beautiful Buddhist sculpture and paintings. Miniature paintings on the statues in the three-story temple inspired the most oohs and aahs. They show court scenes and tantric positions, though why naked women covered the garments of Manjushri, god of wisdom, was beyond me.

On down the Indus—100 km and the longest day of the Zanskar ride—took me to the Dha-Hanu region and a different ethnic group than the Ladakhis. Dha Village, close to the Line Of Control between India and Pakistan, was as far as I could go. The friendly owner of a guesthouse welcomed me in. His mother had been killed in past shelling, and houses had been destroyed from the ground-shaking return fire of the Indians. Things were quiet now, and villagers busily harvested apricots, tomatoes, barley, and animal fodder. Many flowers bloomed in the fields, and the women and a few older men stuck flowers into their hats—looking not unlike walking flowerpots. The canyon of the Indus reminded me of the Grand Canyon—a roaring silt-laden river surrounded by colorful and contorted rock layers towering far into the sky. There's a lot of geology to be seen!

Retracing part of the route back up the Indus and a right turn on the Leh-Srinagar road took me into a narrow and very deep series of canyons. Retracing part of the route back up the Indus and a right turn on the Leh-Srinagar road took us into a narrow but very deep series of canyons. Then came a climb that wouldn't quit. The road twisted and switchbacked higher and higher—no mercy for a tired cyclist. Shortly after dark a woman in Lamayuru found us and showed us to a room in her guesthouse. Next morning I climbed to the large monastery complex to enjoy the views and to step inside to hear monks chanting from their Tibetan books.

Continuing westward, the road maintained its tough climb to the heights, finally reaching Fotu La (Pass) at 4147 meters (over 13,000 feet). A fun downhill didn't last long and soon enough I was winching up the Namika La (3750 m, over 12,000 feet) in a desolate world of dried mud hills. The green valley of Mulbekh came as a welcome sight. It is famous for a large and well preserved statue of the future Buddha, Maitreya, carved in a hillside and between 1000 and 2000 years old.

Beyond Mulbekh I left the Buddhist region of Ladakh and entered the Muslim area of Kargil. Most people follow the Shi'ia branch of Islam and have close ties to clerics in Iran. For the traveler, however, the Muslims here had the absolutely worst behaved children I've ever encountered. The ill-mannered kids—and some adults—constantly begged for pens or sweets. A few stones whizzed by too. Kargil, a dirty, scruffy town, has often been a target for Pakistani artillery in the past. It offered some nearly empty hotels and a busy market, but nothing else for the traveler. Srinagar and its famous houseboats on Dal Lake were only two or three days riding farther west, but I decided not to visit that unhappy land.

Instead I turned south up the Suru Valley toward Zanskar. Poorly behaved Muslim kids harassed me for pens in the villages. Between settlements, though, I could enjoy the splendid views of the mountains and the green fields of the valley floor. Normally the drive by bus or car takes at least 12 hours from Kargil to Zanskar for the 234 kilometers, but not today. I hadn't paid much attention to the thunderclouds the evening before, but deluges 60 km south had blocked the road with mudslides in half a dozen places. No problem for me—I just clambered over the mud and rocks to continue merrily on my way. I stopped for the night at Panikhar, one of the last major Muslim villages. Some young men here were training to be mountain guides—the area has immense potential for trekking—but these guys were just as bad mannered about begging for pens as the smaller kids. I suspect the only things they'll be guiding into the mountains are the family goats. Such stupidity.

Beyond Panikhar the road, now rough gravel, crosses the Suru River, which squeezes through an incredibly narrow gorge only a meter wide in one spot! Around the bend, massive Parkachik Glacier winds down from the Great Himalaya Range to the river's edge. Yet wildflowers bloomed on the other bank of the Suru. It was a day of glaciers—constantly coming in and out of view—with peaks over 7000 meters on the right and nearly 6000 meters on the left. Bessie Too was in her lowest gears as I ascended higher and higher along the raging river. Much, much later I came out into a broad grassy valley in which the river lazily drifted along. This was marmot country—the chubby brown animals stood on their hind feet on the lookout for cyclists or other curiosities. Sharp calls, like police whistles, sounded the alarm before they dove into their burrows. A gateway of Buddhist prayer flags welcomed visitors into this treeless land. I was very tired on arrival at Rangdum Village, which had a tourist guesthouse with running water (in the ditch outside) and electricity (my flashlight). Two tiny restaurants provided basic sustenance.

The next morning I continued past Rangdum Gompa (also the local school) and another village before the gentle climb to Penzi La at 4400 meters (14,000 ft.). Lots of marmots, some small lakes, and good views at the pass, but the most impressive spectacle was a bit farther on as the road swooped high above the Darung Drung Glacier. It's not often that a cyclist gets a bird's-eye view of a massive river of white ice curving down to the valley floor. The muddy waters churning out from the glacier mark the beginning of the Stod River, a major tributary of the Zanskar, which I had seen at its confluence with the Indus. Although now in Zanskar region, the main town of Padum was still far away. After camping a night, I zipped on down the long, straight valley to Padum, reaching it the next morning. There wasn't much to do in town but relax. I visited a couple of gompas (Buddhist temples) nearby, but few monks were about and the shrine rooms were locked. Then came the question, how to get back to Leh? The answer was the same way I had come in—the only road access!

On the way back, the guesthouse at Rangdum was full, and a local policeman invited me to stay in his family's home. His house was much like those in the rest of Zanskar, Ladakh, and Tibet—a flat-roofed two-story structure with thick mud-brick walls painted white. Family life centers around the kitchen stove; all the kitchenware, including beautiful brass pots, was on display in shelves and cabinets. The only pieces of furniture are small low tables; people sit and sleep on the carpets. One member of the family was a lama, and the house had a shrine room with small Buddhist statues and thankas. In the morning a woman fixed Tibetan bread for breakfast and for lunch later in the fields. If you'd like to cook flavorful Tibet bread at home, just gather up a pile of dried cattle dung, make patties from flour dough, cook on a thin rock slab over the dung fire, then char slightly on the burning dung. Really, they did taste good! The composting toilet is in a back room—just a hole in the floor. There's no bathroom—mountain people seem to just wash their hands and face from a basin in the kitchen or in a stream outside. The roof was piled high with vegetation to feed the cows, yaks, and sheep during the six-to-eight-month winter. As it gets very cold outside then, the animals get to stay in the house, but only in the downstairs rooms.

Now I'm back in Leh resting up from the Zanskar adventure, and planning the next excursion—a visit to the Nubra and Shyok Valleys to the north. If I can make it over the pass, that is. The Ladakh Range stands in the way and the only road across it goes WAY UP to 5602 meters (18,300 ft.). This is said to be the world's highest road pass! Will I make it?

Traveling "upper class" is popular in fine weather.

Terraced fields of Dha Village above the swift Indus River.

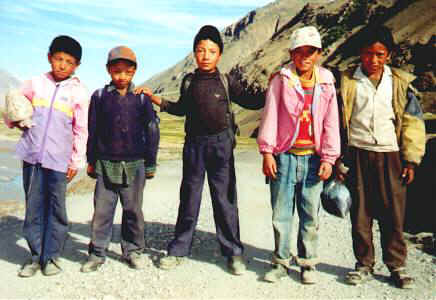

ladies

of Dha Village

ladies

of Dha Village

A road crew—tough guys doing tough work.

These men endure temperature extremes,

boiling tar, thick smoke, landslide danger,

and loneliness to maintain the roads

of the Himalaya. They come from Bihar, which has

a reputation of being the poorest,

most overpopulated, and most corrupt state in India.

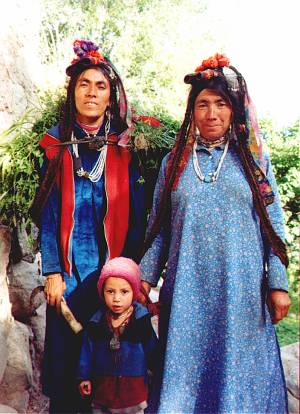

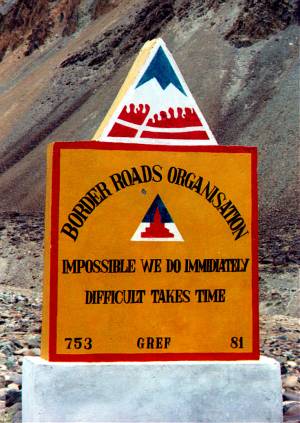

Bits of highway wisdom are a common sight.

Bits of highway wisdom are a common sight.

Lamayuru Gompa is famed for its setting and collection of frescoes, thangkas, and

carpets.

One of four guardians that flank a chapel entrance at Lamayuru Gompa.

Maitreya,

the Buddha of the Future, stands 8 meters tall on this cliff face.

Maitreya,

the Buddha of the Future, stands 8 meters tall on this cliff face.

This is about

the half-way point between Leh (Ladakh) and Padum (Zanskar).

Ulli

and Jeroen of Holland cycle where few others would dare. I met them outside Lhasa

in 1999, after they had cycled across western Tibet from Kashgar. They did it with

crummy Chinese bikes and home-made panniers. The fact that long stretches of road

were washed out and had no shops or restaurants didn't faze them. This year (2002)

they had pedaled across eastern Tibet, an extremely mountainous region. After that

warm-up, Ulli and Jeroen came to the Indian Himalaya and started up the trekking

trail from Darcha (south of Zanskar) to Padum. Well, it took more than knobby tires

to tackle those hills, and the pair had to hire some horses to carry the cycles

and gear to Padum.

Ulli

and Jeroen of Holland cycle where few others would dare. I met them outside Lhasa

in 1999, after they had cycled across western Tibet from Kashgar. They did it with

crummy Chinese bikes and home-made panniers. The fact that long stretches of road

were washed out and had no shops or restaurants didn't faze them. This year (2002)

they had pedaled across eastern Tibet, an extremely mountainous region. After that

warm-up, Ulli and Jeroen came to the Indian Himalaya and started up the trekking

trail from Darcha (south of Zanskar) to Padum. Well, it took more than knobby tires

to tackle those hills, and the pair had to hire some horses to carry the cycles

and gear to Padum.

All you need to make Tibetan bread are some cowpies for fuel,

a stone slab,

and a little flour and water for the dough!

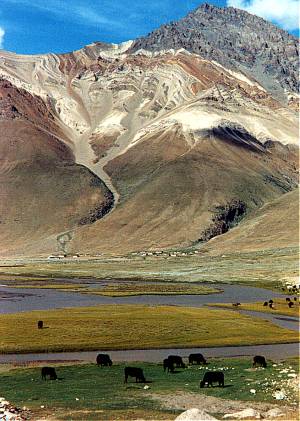

Yaks graze near the last villages between Rangdum and the Pensi La.

This stupendous view of Darung Drung Glacier greets you just past Pensi La.

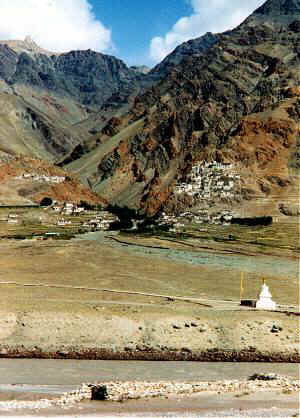

Karsha Village (left) and Gompa (right), just north of the town of Padum in the

heart of Zanskar. The gompa dates back to about the 11th century.

Friendly monks at Likir Gompa. Founded in the 14th century,

Likir is famous

for having magnificent architecture and artwork.

I stopped here on

the way back from Zanskar to Leh.